My 2021 Year-End Giving Summary

In 2019, I started giving 10% of my income to charity. At the end of each year, I write a post outlining where I gave and how my giving philosophy has evolved since the previous year’s post. This is it!

Where the Money Goes

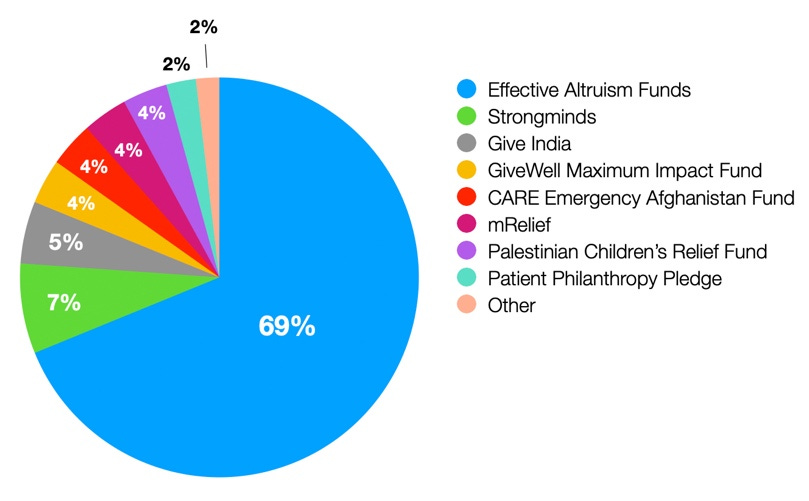

In 2020, I directed the majority of my donations (56%) to the Effective Altruism General Fund. This trend continued in 2021, with 69% of my giving (nice) going there. I donate this way for two reasons: 1) I generally believe in the principles of effective altruism and 2) I am lazy.

This year, I was introduced to two new ideas that have the potential to shift my giving significantly. (Since I learned about each of them relatively late in the year, neither had much of an impact on my overall distributions in 2021.)

The first is worldview diversification, which I learned about in this Ezra Klein interview with GiveWell cofounder Holden Karnofsky. The idea behind worldview diversification is that you should vary your giving according to several different ethical philosophies, just like you’d hold a diversified investment portfolio. In other words, since you presumably can’t be 100% confident in the moral frameworks that guide your giving, you ought to diversify those frameworks.

For example, although I’m semi-vegetarian in my personal life, I’ve never been able to get that worked up about animal suffering. Take chickens: since there are ~10x as many farm chickens on the planet as there are people, and since most of those chickens are kept in far more torturous conditions than any human experiences, it can theoretically make more sense to work towards ending chicken suffering than it can to work towards human suffering, even if you consider the value of a chicken’s life to be an order of magnitude less important than a human’s.

This position makes some logical sense to me, but I just can’t bring myself to care that much about chickens, so historically I haven’t given much towards ending animal suffering. But with the idea of worldview diversification in mind, I’m going to donate more towards that cause going forward. I may as well allot at least a little bit of my money towards the possibility that I might be wrong about this and that the Chicken God is going to punish me severely. I plan to do something similar for philanthropy focused on the super long term, likely through the Patient Philanthropy Fund.

The second big idea was this fascinating report from the Happier Lives Institute, an organization which researches the most cost-effective ways to improve global well-being. The report makes the startling claim that providing psychotherapy to the global poor is significantly more impactful than giving them money. Specifically, they estimate that StrongMinds, which provides free talk therapy (primarily cognitive behavioral therapy) to low-income women in Africa, is 12 times more cost-effective at improving well-being than the cash-transfer provider Give Directly. Since Give Directly is often cited as one of the most impactful charities on a per-dollar basis, this result, if true, would be a big deal.

This report made my mind spin. On the one hand, rich Americans telling poor Africans they really need therapy instead of money strikes me as incredibly paternalistic, and goes against everything I believe about the superiority of giving people money and letting them make their own choices about how to spend it. On the other hand, I’ve personally experienced the benefits that can come from even a little bit of therapy, and it’s not as if access to CBT is so plentiful in these communities that the recipient of a cash transfer could easily go out and find it themselves. On the other other hand, it seems ridiculous to jump straight to the top of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs for people who may still be stuck at the bottom. On the other other other hand, do people not need self-actualization just because they’re poor?

In conclusion, I obviously have no clear conclusions about this report. But in the spirit of worldview diversification, I’ll probably hedge my bets going forward and direct some of my donations towards this kind of work, at least until there’s more research on the matter.

Sticking With It

I have two strategies for actually sticking with a commitment like this once you make it: announce your plans publicly, and make giving a habit.

When I first wrote about my decision to start giving away 10% of my income, I was pretty embarrassed. I was self-conscious that it’d come across as performative, like I was bragging about being a good person. But actually, being so public about my plans has been a good way to keep me committed. If I were to back out now, it would look way worse than if I had never started in the first place.

In fact, the piece has actually saved me from a lot of embarrassment, because now when people try to raise these ideas in conversation with me, I can tell them I don’t really like to talk about it and to just go read my article instead. (There’s nothing people like more than when you tell them to just read your newsletter instead of talking to them like a fellow human being!)

For habit-building purposes, I continue to do all my donating manually—nothing is automated. Every time I receive income, I go make a donation somewhere, and then log it in my donation tracking spreadsheet. While it would technically be “easier” to just have a recurring subscription somewhere, or to donate in one lump sum at the end of the year, I find that doing this unnecessary manual work maximizes the number of dopamine hits I get from my giving, which motivates me to keep doing it. It’s all about finding selfish reasons to do nice things for other people!

Okay, But Where’d the Money Go Really?

Here’s the full breakdown of all my charitable contributions in 2021:

I don’t put dollar amounts in the chart because I’m not (yet) ready to let everyone reading this newsletter infer my precise income, but this year I did achieve my longstanding goal of donating enough that I’ll itemize my 2021 taxes instead of taking the standard deduction. (Re-reading that sentence, it occurs to me that I basically said that I was excited about having forced myself to do extra tax paperwork. This is why people hate effective altruists.)

Anyway. When I first started writing about this stuff, my main motivation was to normalize this kind of giving, and to create social pressure for others to do something similar. I’ll likely never donate 50% my income, but I might be able to convince four other people in my income bracket to start donating 10% of theirs, which would have the same effect.

So here’s to that kind of positive peer pressure. And if you do something similar, or are thinking about it, or think my donation strategy is totally wrongheaded and want to yell at me about it, I’d love to hear from you.

Yours in having desperately tried, but sadly failed, to work a reference to the infamous “That’s what the money is for!” Mad Men scene into this piece,

Max