My Favorite Books of 2025

…by which I mean, books I read in 2025, not books that came out in 2025. A completely unhelpful framing for everyone else!

Baby Meets World, Nicholas Day

The first task awaiting every new parent is to decide what to worry about. Luckily, if you’re not sure, there’s an entire industry of books to give you ideas. You can worry about whether your kid is sleeping the right way, or when to give them a phone, or whether or not your choices can be justified by randomized controlled trials. Much harder is finding the book that helps you worry less: I thought Bringing Up Bébé would turn me into one of those chill French parents, but it mostly just made me stress about not being sufficiently relaxed.

Enter Baby Meets World: the best parenting book I’ve ever read, largely because it’s not really a parenting book at all. Instead it’s a work of (very amateur) anthropology, a tour through the wide-ranging child-rearing practices of many different peoples and cultures, across many different time periods.

And I mean wide-ranging. We’re not talking when to introduce solid foods or take away the pacifier. We’re talking giving your newborns twice-daily enemas (the Beng people of Côte d'Ivoire), avoiding eye contact with infants at all costs (the Gussis in Kenya), or swaddling your babies so tightly you can leave them propped against the wall like a forgotten 2x4 (medieval Europeans). And don’t even get me started on pap, which was basically formula before formula: a concoction of flour, mushy old bread, butter, onions, and whatever else was lying around, mixed with beer or water and—since this was obviously pre-bottles—poured down babies’ throats with a funnel.

And guess what? Pretty much all of these babies turned out fine. (I mean, they didn’t all turn out fine, obviously—a lot of them died, but that was because of the poor state of pre-modernity medicine and public sanitation, not anyone’s parenting choices.) Even the ones forced to guzzle beer actually did okay. In medieval Europe, the most dangerous ingredient in pap was actually just… the water.

It’s hard to read this book without concluding that most of the things we stress about as parents don’t matter—and that the things that’ll fuck our kids up the most are probably the practices so embedded in our culture that we don’t even think to question them.

But I’m still not giving my kid any beer. He’ll have to get his alcohol the way God intended: by sneaking it from the pantry when his parents aren’t home and then carefully rearranging the remaining bottles so that we don’t notice anything’s missing.

Cahokia Jazz, Francis Spufford

Historians would have you believe that there are only two ways to make sense of the past: you can see it as the inevitable result of sweeping, structural forces, or you can see it as driven by the willful efforts of the so-called Great Men. But there’s a third option: history as a series of highly contingent, borderline random events, with small, seemingly insignificant moments cascading, butterfly effect-style, until they shake the world.

That kind of story is hard to tell in a textbook, though. It’s much more effectively explored through alternate history. And for the past decade or so, this genre has been having a real moment, with popular stories asking questions like What if the Soviets won the space race?, What if the Axis won World War II?, and What if you woke up in a world where the Beatles never existed, and instead of displaying any curiosity about how this change might have affected other historical events, you just passed their songs off as your own to impress women?

(I will leave it up to the reader to speculate as to why audiences starting in, oh, I don’t know, 2016 might have become especially eager to imagine ways in which world events might have turned out differently.)

So anyway. Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. We’re dropped into a version of the U.S. much like our own, except that this one has a region dominated by a minority ethnic group, complete with its own language and customs, and even its own brand of cigarettes. Two detectives—one earnest and cheery, one world-weary and gruff—investigate a murder case, which spirals from a run-of-the-mill killing into a grand conspiracy involving powerful political figures, shadowy institutions, and maybe—just maybe—even supernatural forces, all with ominous implications for the region’s long-term sovereignty. And, as in any good detective story, substantial quantities of alcohol are consumed throughout.

Of course, I’m not talking about The Yiddish Policemen’s Union—as you probably gathered from the title of this section, which I’m now realizing spoiled this dumb bit before it even got started—but about Cahokia Jazz, which—though I’m sure the author hates when people describe his book this way—is basically The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, but with Native Americans instead of Jews.

Although I quite like both books, Cahokia Jazz’s much earlier (implied) departure point means it does a much better job imagining how culture evolves over time: YPU’s Alaska Jews are basically just regular American Jews from the actual world, whereas the Cahokians are a strange blend shaped by hundreds of years of counterfactual history. (For example, Cahokia ends up with a significant population of both Irish immigrants and escaped slaves.) This is a great read for alternate history buffs, detective story enthusiasts, and antisemites who like the idea of The Yiddish Policemen’s Union but want a less Jewy version.

Parkland, Vincent Bugliosi

And speaking of alternate histories: only 29% of Americans believe Lee Harvey Oswald shot JFK alone, so you could say that, by the public’s standards, the Warren Report is itself a work of alternate history. Reading the whole Warren Report sounds too boring even for me, someone hovering at the outer limit of how interested you can be in the JFK assassination without tipping fully into nutcase territory, so instead I settled for Parkland, a minute-by-minute account of the days leading up to, and immediately following, the killing. And I mean “minute by minute” literally: the 504-page book covers roughly 72 hours, with almost every minute getting its own thoroughly-detailed section. Bugliosi was inspired to write the book after playing the part of the prosecutor in an unscripted 21-hour mock TV trial of Lee Harvey Oswald, a role he took after his career as an actual lawyer imploded in scandal.

As you might expect from a book that spends seven pages covering the sixty-second period between 1:38 and 1:39pm, I learned a lot from Parkland. More than that, though, this is the only media I’ve ever consumed about the JFK assassination that genuinely moved me emotionally. I can’t exactly say I recommend this book to the general reader, as you have to be a very specific kind of person to get into it. But unfortunately for me and my loved ones, I am that kind of person.

Rejection, Tony Tulathimutte

Every fiction writer, even the amateur ones whose only readers are the dozen or so other hungover kids in their college creative writing workshop, worries that others will interpret elements of their work as, well, not so fictional. It’s terrifying to reveal parts of yourself in a personal essay, but at least that’s on purpose. Far more terrifying is the fear that your fiction may have accidentally revealed your psyche’s deepest and most disturbing abscesses without your even realizing. Shouting “It’s fiction, it’s fiction!” will be no defense—after all, even if the sick and twisted things you put in your writing aren’t true, doesn’t it say something about you that you’re even capable of coming up with such fucked-up ideas?

This is why I think Tony Tulathimutte might just be the bravest writer alive today. Rejection—a set of interconnected stories about unsympathetic malcontents at the bottom of the modern sexual pecking order suffering egregious, self-inflicted humiliations—contains thoughts I would be embarrassed to admit I was even capable of thinking, let alone writing down, most notably in a fourteen-page tour de force that is undoubtedly the most deranged sexual fantasy ever committed to the page. I am honestly a little worried that even just recommending this book reflects poorly on me, but it is really, really good.

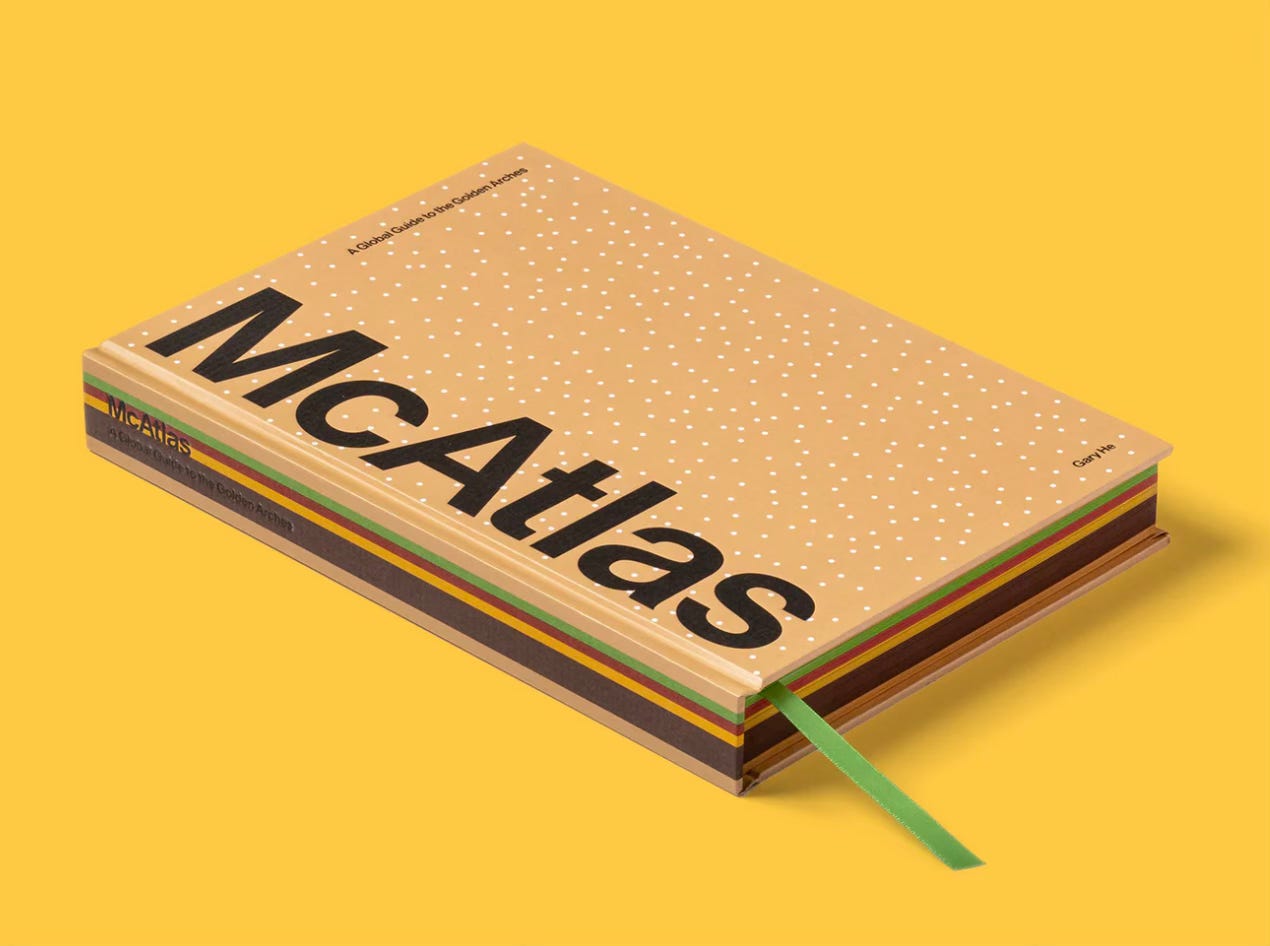

McAtlas, Gary He

The delicious paradox of McDonald’s is that, on the one hand, it’s the ultimate symbol of globalization—Thomas Friedman’s “Golden Arches Theory of Conflict Prevention” posited that no two countries with a McDonald’s have ever gone to war, though that was only debatably true when he proposed it in 1999, and it’s definitely not true now post-Russian invasion of Ukraine—but at the same time, it’s so wildly customized for each of its host countries that it’s simultaneously a great illustration of cultural difference.

I almost never visit a new country without stopping to check out the local McDonald’s, and there’s often a kind of uncanny valley effect where the half-familiar food of a foreign McDonald’s somehow feels more foreign than a completely new cuisine. It’s like when you have a dream where you encounter someone who both is and isn’t your ex-girlfriend at the same time.

Anyway, is it weird to put a coffee table book on my “best of” list? McAtlas is a photo book of unique McDonald’s locations around the world—with a truly brilliant cover/spine design:

This book is basically Baby Meets World, but for McDonald’s instead of children. Wow… see how I brought everything full circle there? I bet you thought I wasn’t going to find a way to tie this all together, but I totally did.

If you liked this, I review every book I read (usually much less thoroughly than this) on my Goodreads.