Political Memoirs, Reviewed

You’re reading Candy for Breakfast, a newsletter about funny feelings, weird careers, making art, American history, and how to be alive. A quick announcement: at 1:30 pm Eastern on Tuesday June 18, I’ll be leading a Zoom session for Foster on doing weird things with metaphors. It’s open to the public, so RSVP here if you’re interested.

In my darker moments, I fantasize about running for office, just so I could write a memoir about it afterwards.

Don’t get me wrong—I know I could never actually do it. I doubt I’m capable of the level of self-restraint a political candidacy requires, and besides, this newsletter alone is an opposition researcher’s wet dream.

But if I did have a political career, I’m pretty sure I could write a great political memoir.

That isn’t as much of a brag as it sounds like. The genre is uniquely terrible, so the bar for a top-tier one is pretty low.

If the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results, then my particular insanity is that I keep reading political memoirs despite so often being disappointed. Here are a few I’ve read lately, and my assorted thoughts on each.

How Not to Be a Politician, by Rory Stewart

Featuring by far the best cover of any political memoir I’ve read, How Not to Be a Politician is the story of Rory Stewart, the mop-haired, almost parodically British-looking MP who ran against Boris Johnson for the 2019 Conservative Party nomination and got absolutely destroyed.

The strength of How Not to Be a Politician is that Stewart, having presumably put politics behind him forever, is unusually willing to shit all over his former colleagues. He tells specific and often quite funny stories of other Members of Parliament double-crossing each other, lying to his face, and being comically image-focused. One of my favorite examples: after hearing every candidate, including himself, use a near-identical slogan on TV, he realizes that Brexit architect and future Johnson advisor Dominic Cummings has fed it to each of them individually, while giving each the impression that he was working with them alone. I also highly enjoyed the moment when, for a few days in 2015, formulating an official response to Cecil the Lion’s death crowds out all other government priorities.

After spending most of my time reading about—and despairing over—the American political system, it was nice to read an equally-pessimistic book about Britain and be reminded that every political system has its issues. The British requirement that every cabinet member simultaneously be an active MP forces Stewart to constantly interrupt his official travel as Minister of State to return to Parliament for often-pointless votes. And the parliamentary system incentivizes cabinet members to constantly scheme against the Prime Minister they serve.

Stewart doesn’t hide his envy of America, particularly despairing at how much better-resourced our government is: during his time in Teresa May’s cabinet, Stewart has to take Ubers because there are no government cars available, relies on Wikipedia because departmental briefs are so lackluster, and learns about important news, like the coup that topples Robert Mugabe, from Twitter.

I liked How Not to Be a Politician, but as with most political memoirs, it’d benefit from being 50% shorter. If you do make it through the whole thing, though, you will be rewarded near the end with this incredible quote from Boris Johnson about his past drug use: “I think I was once given cocaine, but I sneezed and so it did not go up my nose. In fact, I may have been doing icing sugar.”

Forward, by Andrew Yang

I’ll confess to being a biased observer here, having known Andrew for over a decade from my time in Venture for America, and, like most people who knew him from before, having watched his transformation into a political candidate with a mix of befuddlement and delight. It’s bizarre, watching someone you know as a real person become a national figure, and observing up close the shrinking of their soul that seems to be an inevitable side effect.

Andrew is one of the few large-scale politicians who seemed to be truly themselves on the campaign trail—and one of the few as well who seemed to genuinely enjoy campaigning. Like Rory Stewart, he was a non-politician turned candidate, and that initial unfamiliarity with politics generates the most astute observations about the process.

Forward gives you a window into the thousands of small humiliations running for office requires, like the awkward moment Andrew experienced a thousand times at the start of his campaign, before anyone knew who he was, when someone would ask him what he did for work and he’d have to respond that he was running for president. Or his dawning realization that he is not, as he originally assumed, the CEO of his political organization, but rather the product, constantly directed and handled by everyone else.

This is the rare political memoir that would actually benefit from being longer. The campaign-trail memoir portion of Forward is excellent, but it only makes up around a third of the book, with the rest occupied by the more-skippable manifesto slash platform of the Forward Party, Andrew’s post-campaign organization. I would have loved to read a full-length campaign memoir; in the meantime, I recommend the first 30% of Forward.

Politics and Pasta, by Buddy Cianci

If you’re not from the east coast, you may be sadly unfamiliar with Buddy Cianci, the longest-serving mayor of Providence, Rhode Island, who presided over significant improvements in the city’s fortunes but also managed to get himself enmeshed in a truly incredible number of scandals. There were the serious racketeering and corruption charges that eventually sent him to federal prison, but there were also some hilarious small-bore scanda;s, like “Mayor’s Own Marinara Sauce,” the jarred tomato sauce line he launched while in office. Profits from the sauce were to be donated to charity, but due either to creative accounting or genuine incompetence, the line made a grand total of $3 in profit.

It was all worth it, though, because Cianci emerged from prison to write far and away the best political memoir of all time (sorry, Barack Obama). The book is full of incredible details, like when Cianci defends himself against charges that be beat his estranged wife’s lover with a fireplace log by claiming that although he did break into her house and wildly swing the log near the man, he never actually hit him with it, or the time he ended a garbage strike by having shotgun-armed cops ride in trash trucks driven by union scabs.

Cianci was elected to a second stint as mayor after pleading no contest to charges of kidnapping and torture related to the log incident. He ran again at 73, after serving five years in federal prison on corruption charges, and only lost narrowly. Much of Providence loved Buddy, and after reading this book, I get why. I’m sure 90% of it is a lie, but if he were still alive, I’d vote for him for anything.

Inside the Third Reich, by Albert Speer

We turn now from a charming criminal to a significantly less-charming criminal, Nazi hotshot Albert Speer. Speer started as Hitler’s chief architect and eventually worked his way up to be Minister of War, proving once and for all that there are career paths for architects other than being the male lead in a rom-com.

Speer’s book, while obviously self-serving—he unconvincingly disclaims any knowledge of death camps and the Final Solution—provides a fascinating insight into the mind of one of the less-fanatical Nazis, and into the cultural rot that inevitably seeps into a totalitarian dictatorship.

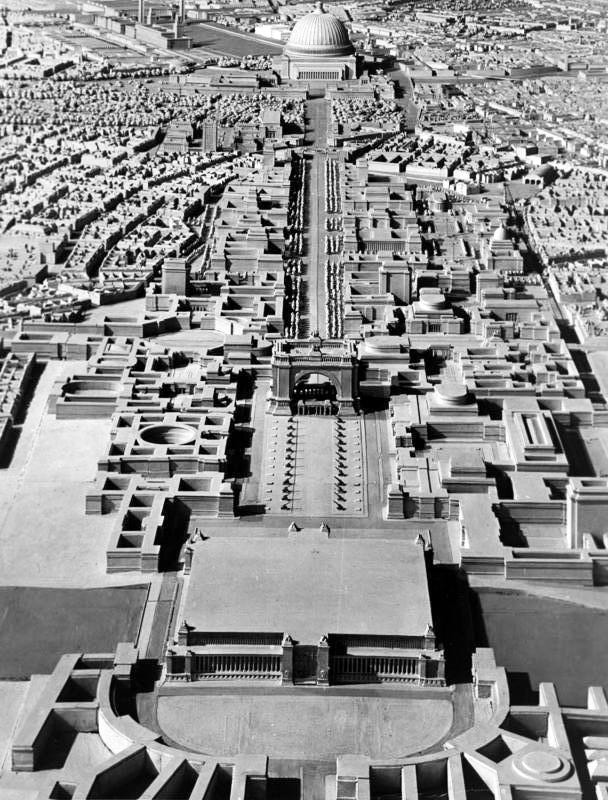

The leading Nazis come across less as evil masterminds and more like little boys playing the world’s most deadly game of dress-up. Even as Germany starts losing the war, Speer remains obsessed with the fantasy Berlin he wants to create, spending far more time than is sensible for the Minister of War designing architectural plans for individual buildings. As the Allies draw ever closer, Speer slips ever further into his dream world, spending hours each day on a small-scale model of his future Berlin that will obviously never be built.

What Happened, by Hillary Clinton

It doesn’t seem like Hillary Clinton actually has a very good understanding of what happened in the 2016 election. One star.

A Promised Land, by Barack Obama

Politicians are not, as a rule, known for their high levels of introspection. Barack Obama is the rare exception, probably our most self-aware president since Lincoln. Like that guy who runs so fast he breaks out of the Matrix, other politicians experience occasional flashes of this—even Trump once said, “I don’t like to analyze myself because I might not like what I see”—but it seems to be Obama’s default mode.

No doubt relatedly, he is also one of the best presidential writers in recent memory. A Promised Land is a beautifully-written book. There is a level of candor and rumination here, of second-guessing his own decisions and motivations, that is highly atypical for a political memoir.

I enjoyed A Promised Land a lot, but in the end, its beautiful prose only highlights the limits of self-awareness. I think Obama was a pretty good president—not an all-time great, but certainly above average. He did some good things, did some bad things, made the heartbreaking moral compromises every president makes. In the end, does it make any difference whether he saw those compromises with clear eyes or not?

Reading his book, I was reminded of another great work about a politician: The Fog of War, Erroll Morris’ documentary about Vietnam War architect Robert McNamara. McNamara evinces a remarkable level of self-awareness: at one point, he admits that, had we lost World War II, he likely would have been tried as a war criminal for his role in the firebombing of Tokyo. You’d like to think that being introspective helps you make better decisions, but McNamara’s life is evidence that this isn’t necessarily the case.

Rapid-Fire Lessons & Conclusions

How Not to Be a Politician: Read about British politics if you want to feel better about American politics.

Forward: If you’re going to run for office, try to have fun while you do it.

Politics and Pasta: If your wife takes a lover, you should probably sort that out with her rather than beat him up.

Inside the Third Reich: Don’t become an architect.

What Happened: If you’re going to write a memoir about something horrible you went through, it takes more than ten months to fully process the experience.

A Promised Land: Self-awareness only gets you so far.