Aliens at Both Ends

Of the many surprises of the past few years, none has been more unexpected than the fact that the 2020s have turned out to be the most exciting time for alien-related news in decades.

It started in 2020, when former Senate Majority Leader (and deeply missed badass) Harry Reid said that the government had been hiding information about UFOs for years1. Then former CIA Director John Brennan went on Tyler Cowen’s podcast and strongly implied that he believes alien activity is a plausible explanation for some of these sightings. Even Obama got in on the action during a very on-brand interview with Reggie Watts.

Obviously, we’re far from having conclusively proven that aliens are real, let alone that they’ve visited us. And after reading about how one of the “UFOs” the Air Force shot down during the Chinese spy balloon hysteria was probably just a $12 balloon from the charmingly-named Northern Illinois Bottlecap Balloon Brigade hobbyist club, I have some questions about how good our government’s flying object identification skills really are. But it’s still pretty remarkable that in a few short years, the prospect of alien visitations has gone from a conspiracy theory spouted only by eccentric Unabomber types to a possibility endorsed by players at the highest level of government.

What’s even more remarkable is that this is only the second-most interesting piece of alien-related news to emerge this decade. Because there are the aliens that come from above—and there are the aliens we create.

Much has been written lately (some of it by me) about the past year’s astonishing progress in artificial intelligence and its implications for our species. Already, people have become convinced that we’re all going to be out of jobs, or that art is now dead, or that talking to AIs will ruin our capacity for human relationships. They have used AI to “speak” with the dead and mourned the loss of their AI girlfriends. I have read hundreds of indistinguishable articles by writers concerned that the rise of AI-powered writing will flood the internet with a deluge of… hundreds of indistinguishable articles.

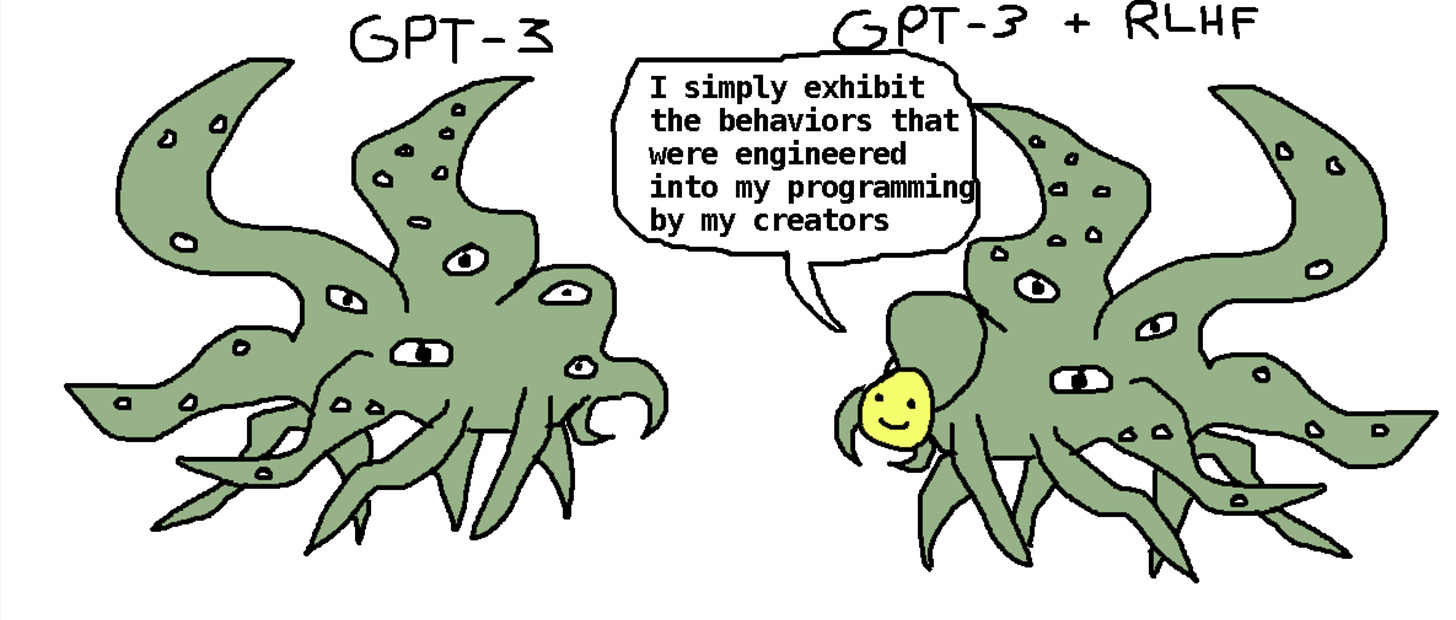

But for all of the human-like things these AIs can do, under the hood, they aren’t human-like at all. No one, not even the engineers who program them, really understands how they work. Finally, the engineers have joined the rest of the population in its complete inability to understand technology’s inner workings.

I don’t know when we will reach the point where these intelligences will truly be considered beings of their own. I don’t even know how we’ll ever be able to make that call using anything other than guesswork. The various confident pronouncements of these programs’ consciousness, or lack thereof, ignore the fact that we don’t even know what consciousness is2. About the only thing I can really be sure of is that I’m conscious. The rest is an educated guess.

But if and when we do reach that point, I don’t think there will be a better word to describe those beings than aliens.

And so the question is, which will happen first: will we be visited by aliens—or will we create them?

From the day we first conceived of aliens, we worried that they might kill us. As early as the 2nd century, the Syrian author Lucian of Samosata wrote of stumbling into a space war between the people of the Sun and the people of the Moon. In Voltaire’s Le Micromégas, a giant from Saturn considers stamping out human armies in frustration at our species’ inability to make peace. And of course there’s the infamous story of Orson Welles’ 1938 War of the Worlds radio drama, long held to have incited a panic among an audience that believed its reports of a Martian invasion to be real—although there’s little evidence that the “panic” was anything more than a few confused listeners.

And now it’s the AIs who we worry might kill us all, either because they’re nothing like us or because they’re too much like us. There is a deep irony to the fact that these AIs learn by ingesting all of the text on the internet, which includes all that stuff we’ve written about how they might extinguish us; if we accidentally teach them to turn on us by having documented that very fear, it will be an end to our species worthy of the finest Greek tragedies.

Some believe this possibility, however remote, means we shouldn’t create artificial intelligence at all. I wonder how those same people feel about the prospect of making contact with aliens. Do they believe in the “dark forest,” the metaphor from Liu Cixin’s excellent Three Body Problem trilogy? In the books, the Fermi paradox is resolved by picturing space as a quiet forest at night. Any animal that makes its presence known is likely to get eaten before it even realizes what happened—so the only winning strategy is to hide indefinitely. Thus, whenever life in the universe becomes intelligent enough to potentially make contact, it’s either smart enough to hide, or else it promptly gets extinguished.

Before we conceived of aliens, there was another hypothetical superintelligence we worried might harm us—one who it was said had already come very close to wiping out all of humanity on at least one occasion. That superintelligence was, of course, God. And it’s God I always think of when I read the arguments between those who insist artificial intelligence portends our doom as a species and those who are equally insistent it doesn’t. The people who make these arguments are educated and intelligent, scientists and researchers, but their debates remind me less of science and research than they do of the Talmud: a bunch of learned, erudite men (and they are mostly men) arguing over the minutiae of something they barely understand and can’t even be sure actually exists at all.

And so the only real side I can take in the debate is the same one I take in the debate over the existence of God: a throwing up of one’s hands and an exaltation of “who knows?” But really, whether I, or anyone else, thinks creating AI is worth the risk is beside the point. Our walking this path is inevitable. We are simply not a species who holds off on doing what we want to do—or, especially, learning what we want to learn—because of the risk it might go wrong. From the very first human, we have bitten right into the apple even when we knew we probably shouldn’t.

And since I know I can’t change that, I choose to embrace it. If there is a collective purpose to our species’ existence beyond just trying to build a world with less suffering, it has to be discovering as much of the underlying truths about this universe as we can. Creating artificial intelligence is part of that discovery.

Curiosity, after all, is one of the most powerful motivators there is. I want to talk to aliens, no matter whether they come from the sky or from my computer. And if they kill me, or all of us, afterwards? I’ll throw up my hands and laugh and say, “Alright, alright, you guys, gotta hand it to ya—you got me.”

Fun facts about Harry Reid: he once choked a man who tried to bribe him, Scorsese cited him as an inspiration for one of the characters in Casino. and he told a roomful of donors, unprompted, that Kirsten Gillibrand was the “hottest senator.”

It’s telling, though, that all the musings about these programs’ potential consciousness focus on ChatGPT and other text-based tools. I’ve never heard anyone suggest that the image-generation tool DALL-E might be conscious, even though it’s equally advanced under the hood.