Even Cleveland

Or, how I learned to like everywhere

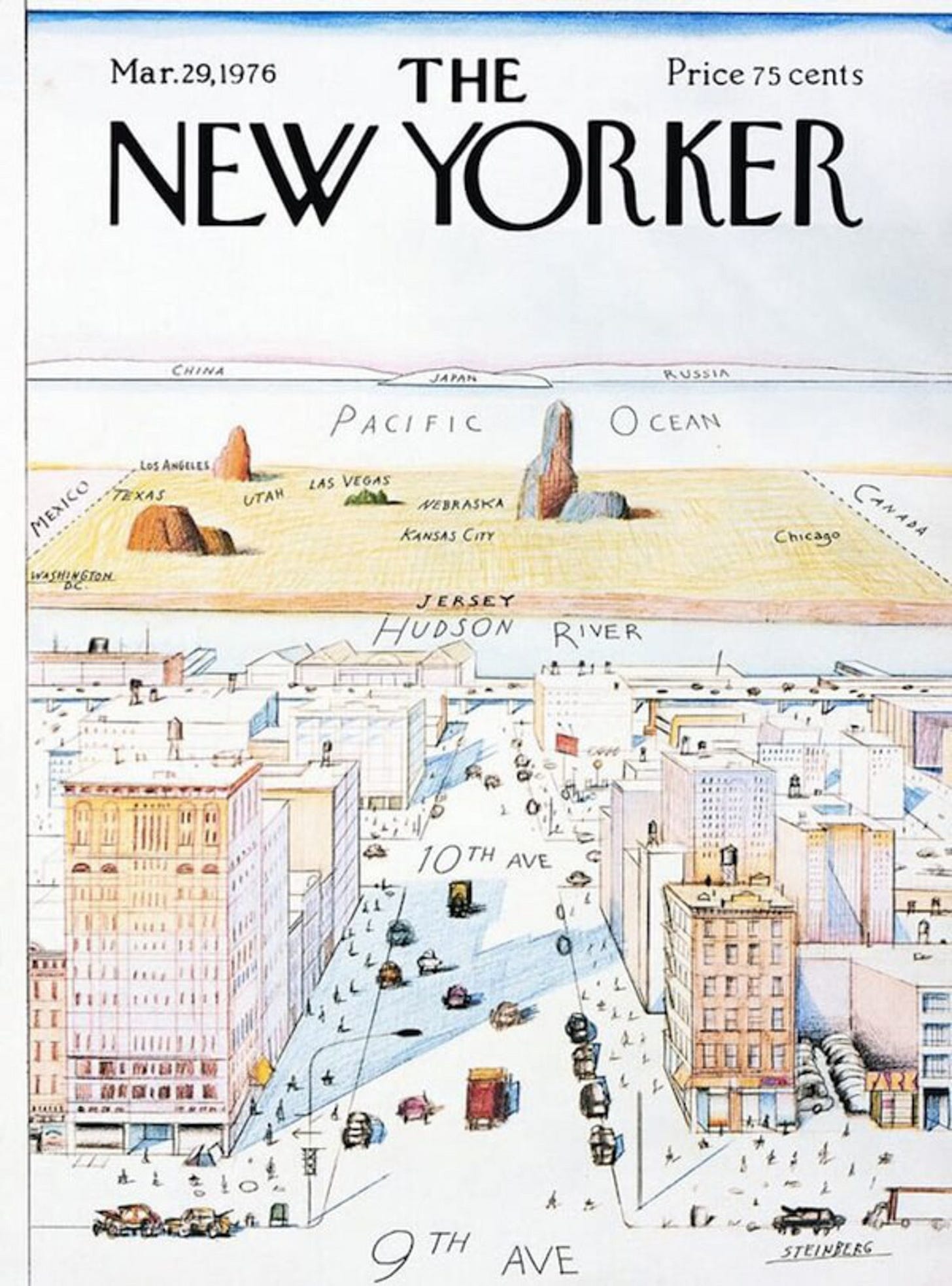

I grew up as one of those coastal elites that Republicans railed against during the 2004 election—the year I started high school and the year John Kerry learned that no one ever looks cool windsurfing. You know the type: we unironically used the term “flyover country,” shared that map that had all the blue states joining Canada, and laughed knowingly at that New Yorker cover that showed everything west of the Hudson compressed down to the size of a single New York block.

I had a print of that cover on my wall when I was 22, the year I graduated college and moved to Detroit. I had traveled a decent amount by then, but I had always prioritized trips outside of the U.S.; like many in my milieu, I had probably been to more European countries than American cities.

I landed in Detroit almost randomly, having impulsively joined the first class of the entrepreneurship fellowship Venture for America, and while I had managed to get myself excited about Detroit specifically, I was still so-so on the rest of the country. Detroit was a one-off deviation from my dislike of “real America,” the exception that proved the rule.

But then VFA gave me friends all over the country in a lot of overlooked places—Cleveland, Columbus, St. Louis, San Antonio, downtown Las Vegas—and I started to visit them all, more out of a desire to see my friends than out of a desire to see the places they lived. But the more I traveled, the more that changed, and the more I realized I pretty much liked everywhere. As it turns out, most places are actually pretty cool.

The idea of travel expanding one’s perspective is a tale as old as time, and one just as cliché as that phrase. But it’s usually told in the context of travel to other countries. For me, though, it was actually travel within my own country that had the more dramatic impact. Somehow, seeing the small differences in how people lived a few states over was more eye-opening than seeing the big differences in how they lived across oceans.

I came to have an extra level of affection for the kinds of places others look down on—underappreciated gems like Detroit and Cleveland—or those that are popular targets of disdain, like Las Vegas and the non-Miami parts of Florida1. I like any place that’s unique and unapologetically itself, which all of those cities are. But of course, perhaps everywhere is like that if you give it enough attention. Sometimes not liking something just means you haven’t looked closely enough.

And it’s not just cities. I even like what French anthropologist Marc Augé2 calls non-places: spaces that are so generic or transitory that they lack the significance needed to meet the anthropological definition of a place. Non-places are anonymous, transitional spaces—malls, hotel rooms, airports. People who hate the suburbs often feel like they’re non-places, although by Augé’s definition you can’t really live in a non-place; making your home somewhere automatically disqualifies. (I’m not sure what he would say about Tom Hanks in The Terminal.)

My favorite non-place is Times Square, which gets a lot of shit it doesn’t deserve from cynical New York types. What’s amazing about Times Square is that it contains both utopia and dystopia simultaneously. Utopia: it’s mostly car-free and probably the most diverse quarter-mile in the world, somewhere you can hear a hundred languages spoken at once. Dystopia: it looks like Blade Runner and no matter what time of day you walk through, you will be harassed by at least one creepy Elmo.

My liking everywhere started as an accident, but it ended up becoming a philosophy. It’s fun to challenge yourself to find the appeal in a place that seems off-putting at first, just like it’s fun to learn to appreciate Hieronymous Bosch or Jeanne Dielman.

Besides, I have this crackpot theory that everything we don’t like in the world is really just something we don’t like about ourselves. We dislike the suburbs because we fear that living there would make us boring. We dislike slow movies because they highlight our own poor attention spans. And it goes without saying that the flaws we find in other people bother us the most when they remind us of ourselves. From this angle, learning to like more of the world is really just learning to like more of yourself.

These days I live in New York, where you often encounter people who insist that this is the best place in the world, people who go on and on about how they can’t imagine living anywhere else. There’s a sense in which they’re not wrong—I don’t know that I’d say New York is necessarily the greatest city in the world, but it’s clearly among a small group of contenders for the title—but whenever I meet someone like this, I can’t help but feel like the main person they’re trying to convince is themselves. Plenty of people in Michigan never leave either, but they don’t make such a fuss about it.

There are times when I worry that I’ve betrayed my “liking everywhere” principles by having landed in such a popular destination. But there’s another way in which living here can be a good litmus test for that creed, and that’s in trying to find the beauty in even the “worst” parts of it. So I try, when I can, to look closely, to find something worth appreciating, in the trash piles, the subway fights, the broken-down infrastructure.

But I still run away as fast as I can when one of those Elmos gets near me.

Las Vegas in particular is such a monstrous aberration that I can’t help but be charmed by it. By any logical measure, it just shouldn’t exist, and the sheer irrationality of the whole enterprise is a glorious middle finger to sanity. If I was a religious person, I might even call it an affront to God. Every time I visit I’m reminded, in a good way, of the Tower of Babel.

Who, by the way, looks like exactly what you’d picture when you hear the words “French anthropologist.”