My 2023 Year-End Giving Summary

This is my 2023 year-end giving summary, an annual update on the how, where, and why behind my 2019 commitment to putting 10% of my income towards various causes I think deserve funding. (I shorthand this as “charity,” but technically not everything I give to is an actual charity.)

Previous posts in this series include why I decided to do this (and why I resisted talking publicly about it at first), as well as where I donated in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

Commitment & Temptation

This was the first year since I began this practice where I had long stretches of being seriously tempted to stop.

Maybe that’s because I took a big pay cut at the beginning of the year to join a friend’s startup, so losing that 10% hits harder than it used to. Maybe it’s because I’ve finally reached the age or life stage where things like buying a house have gone from hazy future aspirations to nearer-term goals. Or maybe it’s just because I’ve now been doing this for long enough that the total amount I’ve donated over the years has grown pretty substantial, and it’s easy to look at that sum and wish I still had it in my bank account.

A few things keep me going. One is sheer inertia, and my having been so public about this that—as was one of the goals behind writing about it—it would be awkward and embarrassing to stop now. The second is the knowledge that this alternate reality where I still have all that money is probably just a fantasy. Realistically, even if I hadn’t donated anything over the past four years, I’d have ended up spending most of the money anyway, and probably not on things that had a meaningful impact on my overall wellbeing.

But of course, the biggest factor is thinking about what kind of person I want to be, and what kind of behavior I want to model to the small part of the world that cares what I do at all.

One of the reasons a practice like this is so effective is that, paradoxically, it feels much worse to start giving and then stop than it does to never have started at all. When you’ve never started, you can tell yourself that you’ll give back someday—you’re just waiting for the right moment. But to start and then stop is to admit to yourself that actually, when push comes to shove, you probably wouldn’t1.

Because if I stopped, when would I start again? It’s easy to tell yourself you’ll start doing something like this later, when you have “enough,” but the definition of “enough” is always changing. When I was in my mid-twenties, making $40,000 a year and donating nothing, the amount I make now would’ve seemed like way more than “enough.” And in retrospect, the $4k/year that such a commitment would have involved then hardly seems like a significant expense.

The Other Side of the Fraction

A mental tactic that’s been helpful for me this year is that every time I start thinking about the extra money I’d (theoretically) have if I gave less away, I try to redirect that energy into thinking about how I can grow my income instead.

After all, people generally get rich by making more, not by spending less. Even if I donated nothing, I’d at most be 10% richer2. Growing my income, on the other hand, has theoretically uncapped upside, and presumably enables me to give away even more.

This may not be the most helpful model if you’re the kind of person whose income is just your one job’s salary. But it’s worked well for me, since I almost always have a couple side gigs going. (Right now, I’m helping founders tell their stories to investors and ghostwriting dating app bios, which, if you squint, are kind of the same thing.)

These only made up around 8% of my income this year, but I have some loose plans to grow that in 2024. If you need help with your fundraising pitch or your Tinder bio, hit me up.

2023 Giving Philosophy

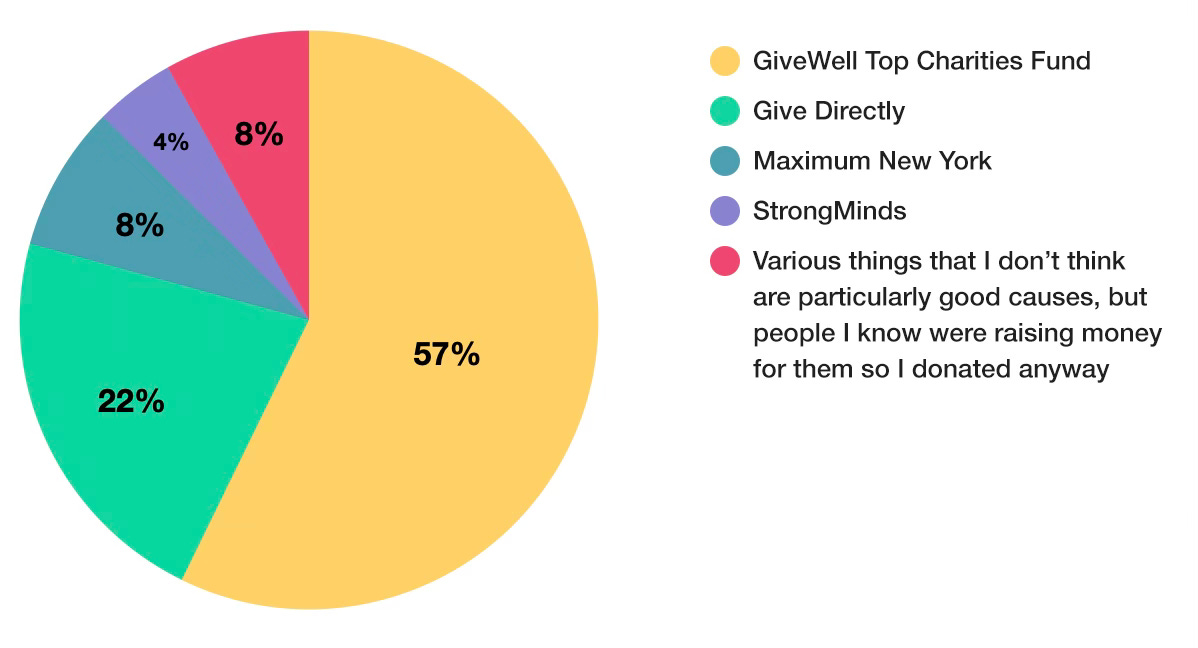

I follow a very loose system of donation ethics that I’ve previously described as “dumb effective altruism.” Basically, it involves taking EA’s foundational insight—that instead of donating to whatever’s in the news or tugging at your heartstrings, you should use evidence and reason to direct your money where it can do the most good—and ignoring all the crazy thinking about existential risk or superintelligent AI killing us all3. As such, the bulk of my giving this year (79%) went to GiveWell and Give Directly, two EA mainstays.

Under the auspices of worldview diversification—basically, the idea that you should build a portfolio of ethical systems to mitigate the risk that your main one turns out to be misguided—I also gave to a few other organizations that are probably less “effective” in the EA sense, but that I think are doing interesting work.

StrongMinds provides free depression treatment to women and adolescents in the developing world. My own experience has taught me that improving your mental outlook can be just as impactful, if not more so, than improving your actual circumstances. If the goal is to reduce human suffering, we may be overinvesting in the material and underinvesting in the psychological.

Of course, you can imagine an idea like this scaled to an almost dystopian degree, where a focus on helping individual people get the mental tools they need to cope with their shitty circumstances is used as an excuse to not actually improve those circumstances—basically, Brave New World, but with therapy and meditation instead of Soma. I also think there’s a very real possibility that American mental health culture has become actively counterproductive, and that exporting too much of it could have downsides. Still, at this point, I think a marginal shift towards more mental health treatment in the developing world is likely enough to be net positive that it’s worth experimenting with.

Maximum New York is attempting to build a better NYC by getting more people involved in local government and teaching them how it actually works. The “organization,” if you can call it that, is tiny—as far as I can tell, it’s just one guy right now, and their entire fundraising goal is a mere $150k. I donated to them because, in addition to liking what they’re doing, I wanted to direct a bit of my giving towards something small and new, where my money could conceivably make a meaningful difference in their ability to exist at all.

Parting Thoughts

Charitable giving is declining in America. In 2000, two-thirds of American households gave to charity; in 2018, fewer than half did. And most people, especially the super-rich, give thoughtlessly and ineffectively—last year, over 10% of all charitable donations in the U.S. went to university endowments. (It is truly mind-boggling to me how any billionaire could look at the vast landscape of potential causes to fund and think, “I must buy Yale a new building.”)

One of the reasons I dislike the modern trend of shaming people who have the “wrong” opinions—or even arguing about politics at all, really—is because I believe that, outside of your closest relationships, there’s only one real way to influence other people: by example.

This commitment, and these pieces, are my small attempt to do just that.

If you liked this piece, click the heart button below to virtue signal that you too are a good person.

Writing this made me curious about the etymology of the phrase “when push comes to shove.” Turns out it’s from rugby! After a player breaks the rules, forwards from each team face off and push against one another until one of them can kick the ball out and resume the game.

Actually not even, because donating this much gets you a big tax deduction.

For what it’s worth, I actually do think x-risk concerns are valid, but because they’re so unpredictable and hard to quantify, I suspect that most efforts to address them directly are hopeless. The best way to mitigate these risks is just to build a prosperous society with stable, well-functioning institutions, so that we have a decent chance of addressing such issues if and when they actually arise.