Sketches from Parenthood, Months 2–6

From oldest young person to youngest old person. During my last few years of childlessness, I was surrounded by twenty-year-olds everywhere I went—cool, hot twenty-year-olds, with mysterious slang and incomprehensible fashion choices—and it got hard to find anywhere to go or anything to do that didn’t leave me feeling like an ancient, rotting husk. I was worried that becoming a parent would accelerate this process, but to my surprise, it’s actually left me feeling younger than I did before.

Maybe that’s because I’ve gone from the tail end of one phase of life to the beginning of the next. Or maybe it’s just that, at 35, I’m actually kind of a young dad by New York standards, with hopefully at least a few more years to go before I develop the evasive hair and sad little paunch that defines so many of the middle-aged men I see pushing strollers in the street.

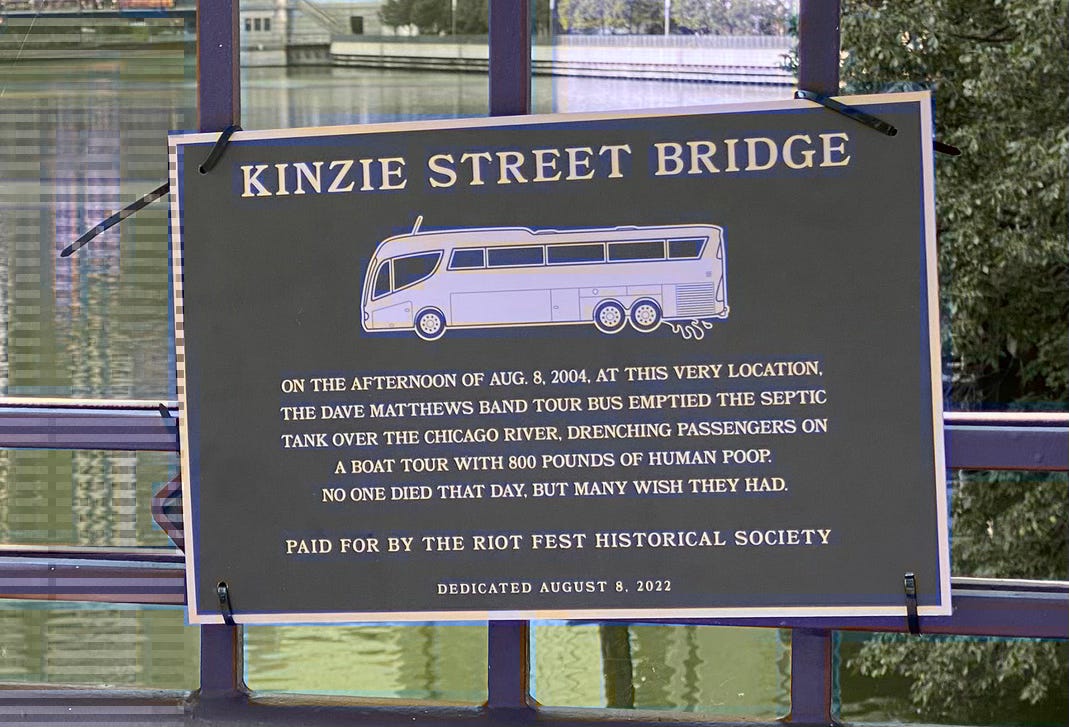

There’s one thing that does make me feel super old, though: thinking about how events I lived through will only ever be distant history to my kid. To him, 9/11 will be as far back in the past as the Vietnam War was to me, and the single most defining historical event for all millennials—the time Dave Matthews Band’s tour bus dumped 800 pounds of human waste onto an open-top sightseeing boat—probably won’t even make it into his textbooks.

The other day, I was in the car with him listening to “The Real Slim Shady,” and I thought about how to him, Eminem will never be anything but lame old-person music, and the idea that he was once so controversial that he was denounced on the Senate floor by the Vice President’s wife will seem as ridiculous as the idea of 1950s TV stations cutting away from Elvis’ wiggling hips.

Then again, when I shared this insight with a friend, she was like, “Max… Eminem has been lame old-person music for at least a decade already.”

Are you (emotionally) smarter than a six-month-old? Watching my son go from overjoyed to anguished in an instant—a transition that happens many times a day—two things are obvious. One, he’s usually upset about something extremely trivial, and two, he often has no idea what it is1.

This is one way in which he’s very much unlike me. When I’m upset, I usually know why, and it’s usually some complicated situation related to the specific circumstances of my life—either that, or your standard-issue, garden-variety free-floating existential angst.

At least, that’s what I used to think. Now I’m not so sure. Am I actually better than a baby at figuring out what’s making me upset? Or am I just better at telling myself elaborate lies?

Now that I think about it, when I’m dealing with an agitated adult, I often suspect the real cause isn’t what they’re pointing to. But I rarely turn that same lens back on myself, and maybe I should.

Feeling follows action. An old neighbor of mine, a psychiatrist in training, once told me that we think we treat people based on how we feel about them—but in reality, the relationship is bidirectional: we start to feel a certain way about people based on how we treat them. If you make a habit of being kind to someone you don’t like, you’ll probably start liking them more. That, he told me, is the real reason you shouldn’t be mean to the people you love: not (just) because it hurts them, but because it’ll make you love them less.

I think about this often in the context of parenthood. Saying that I take care of my son because I love him is no more or less accurate as saying that I love him because I take care of him. It’s obvious to me how you can love an adopted child just as much as a biological one, or, conversely, how outsourcing too much of your kid’s care—whether because you’re a one-percenter with a 24/7 live-in nanny or just a fly-by-night father who doesn’t change diapers—could make you feel less connected to them.

This idea probably has applications in areas other than childcare (Cate Hall recently wrote a fantastic piece exploring similar themes in the context of romance), but I will leave figuring out what those are as an exercise to the reader.

My second-greatest parenthood fear. My greatest fear as a parent is that something horrible will happen to my child, like getting hit by a truck, or growing up to be one of those guys who sells nitrous balloons in the parking lot outside Phish shows. But my second-greatest fear is that I’ll end up writing about parenthood in a really lame way.

Having a baby has been one of only two experiences I’ve ever had where pretty much all of the clichés have turned out to be true2, and “it’s just like everyone says” doesn’t make for very interesting writing. But also, I just like parenthood so much, and it’s hard produce good copy about something unambiguously positive. There are very few best-selling memoirs about happy, low-conflict marriages, or people who did a bunch of drugs, had an awesome time, and didn’t suffer any negative consequences.

Of course, it’s not like I expected to dislike parenthood. It’s just that I expected to like it the same way I like everything else: in a considered way that leaves plenty of room for nit-picking and criticism. I assumed that, as with most things, there’d be good parts and bad parts, and that on net, the good would outweigh the bad. Instead, it almost always feels like it’s exclusively positive.

Note that I said it feels that way, not that it is that way. On some level, I can tell that my subjective perception of experiences has become untethered from reality in a way that would honestly be a little concerning if it happened in any other context. Obviously, some part of me understands that having a baby brings certain downsides, like sleeping less, and getting pooped on significantly more than you used to. But somehow, they almost never feel like downsides in the moment. Even the poop one.

Because I’m edgy and cool and not like the other dads, I previously compared parenthood to taking psychedelics, and this gulf between the valence of an experience as I intellectually understand it and as it feels in the moment is another such parallel. Once, in my mid-twenties, I stood in the freezing rain for hours, waiting for a Killers concert to start, thinking, “I am very cold and very wet and that is unpleasant,” but somehow loving it all anyway.

Parenthood is just like that concert, is I guess what I’m saying. Only way more expensive, and you’re wet from pee instead of rain, and you live at the venue forever now.

This is the third entry in what I guess is now a trilogy about parenthood. If you liked it, check out Having a Kid Is Already Fucking Me Up and He Hasn't Even Been Born Yet and Sketches from Parenthood, Days 1–30.

His list (hungry, frustrated, lonely, tired, wet diaper) bears an uncanny resemblance to the HALT acronym (hungry, angry, lonely, tired) used in addiction recovery to spot the warning signs of relapse. Though as an adult, wetting yourself is more often the result of a bender than it is the precursor to one.

The other was visiting Portland.