So You Want to Be a Machine Politician

Everything you didn’t realize you wanted to know about mid-century machine politics

You’re reading Candy for Breakfast, a newsletter about funny feelings, weird careers, making art, American history, and how to be alive. This is another long one, folks, with a lot of footnotes. I recommend clicking the title above to read it in the browser instead of in your email.

You wake up sweaty, tangled in dirty bedsheets, your head spinning. What happened last night? Where are you? Who are you?

As you stagger to the bathroom and splash water on your face, you start to remember. There was that weird guy outside the bar last night… buzzes and flashes… something about a time machine… you shouldn’t have agreed to try it, but hey, it’s hardly the craziest thing you’ve tried after six whiskeys…

You look in the mirror, and that’s when it hits you. You’re not in 2024 anymore—you’re in 1965 Chicago. And you’re no longer an effete, overeducated Substack reader—you’ve transformed into a young, working-class Irish immigrant. (Or, if you already were a working-class Irish immigrant, then nothing has changed except that now I feel bad about having stereotyped you.)

Where just a moment ago you were a complacent member of the laptop class, the new you is full of ambition and grit, eager to rise beyond the station you’ve been born (er… time-traveled) into. But how? You want something more than the life of your working-class peers—barkeep, factory worker, longshoreman—but a professional education is out of reach.

Luckily, there’s one career path that will let you rise above your station without a formal education. All you need is a willingness to work your ass off and a flexible moral compass.. That’s right: it’s time to enter the exciting field of local politics.

And local politics means the machine. Everyone knows what the machine is, but it’s such a part of life that they don’t even think of it as “the machine”—it’s just the way politics in Chicago always has been and always will be.

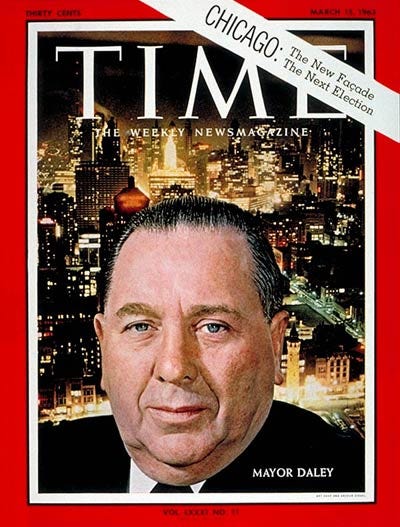

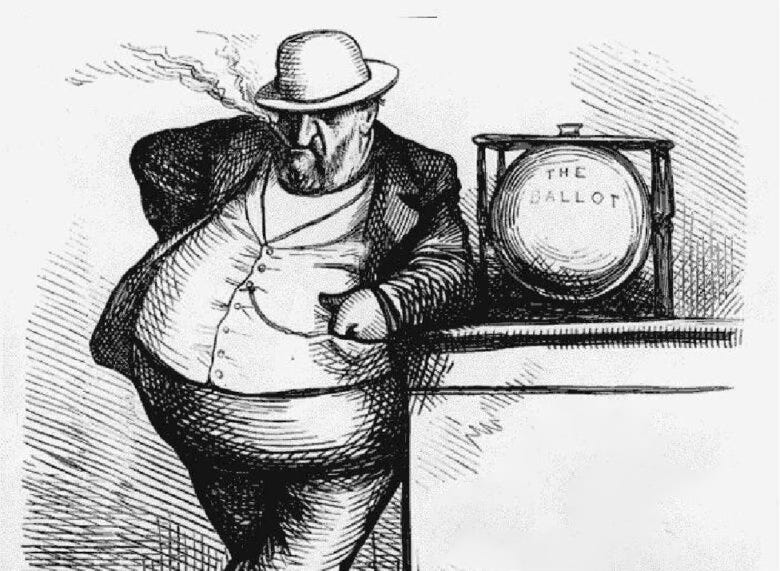

The machine is the confederation of organizations and politicians that dominates Chicago. At the top sits the only mayor you’ve ever known, sixth-termer Richard J. Daley. Pretty much no one gets elected to office, passes a law, or even fixes a pothole without the machine’s say-so. Once, every big city had a machine, but by now government reforms, legal investigations, and cultural shifts have brought the rest down: Philadelphia’s bosses have been tamed, Boston’s Curley Machine couldn’t survive its namesake’s imprisonment on bribery charges, and reformer slash future airport icon Fiorella LaGuardia has dismantled New York’s Tammany Hall.

Only Chicago’s remains. And it just might be your ticket to riches—or at the very least, to a better life than the one your parents had.

Luckily, you have a guide with you. The time machine seems to have consumed most of your possessions, but one made it through: Milton Rakove’s 1975 book Don’t Make No Waves, Don’t Back No Losers, an insider’s account of the Chicago machine’s inner workings.

And so, with Rakove as your guide, you begin your journey.

Becoming a Candidate

In the world of the machine, becoming a candidate for office requires two things.

These aren’t the things you might expect, like policy positions or a campaign organization. For now, there are only a handful of “voters” you need to convince: the dozen or so men who dominate the Cook County Central Democratic Committee, the machine’s main organization. If those guys decide to slate you for office, you’re pretty much guaranteed to win: they’ll clear out the competition and put their powerful get-out-the-vote operation behind you. If they decline to slate you, you don’t stand a chance.

These party men want you to have the right ethnic background and a proven track record of loyalty. Or, alternatively, you could just be rich: men have been known to buy their way into office with a generous donation to the party coffers. But since you can’t Mike Bloomberg your way into office, ethnicity and loyalty it is.

There is no one “right” ethnic background. Any ethnicity with voting power in the city can work, in theory: Polish, German, Italian, Jewish, even Black. But the best option is to be Irish, so it’s a good thing that’s what the time machine made you. The Irish are the largest ethnic group in the city, and thus the dominant force in its politics1. Hence the old saying about Chicago: “The Jews own it, the Irish run it, and the Blacks live in it.”

With your ethnic credential secured, it’s time to prove your loyalty to the party. And there’s no question about which party. Vaudeville comic Will Rogers once joked, “I am not a member of any organized political party—I am a Democrat,” but Will Rogers never lived in Chicago. Chicago is a one-party town, and the machine is the Democratic machine.

It’s not just Chicago—almost every big-city machine was Democratic. Why the Republicans never managed to develop their own machines could be an entire essay in itself, but the biggest factor was the way machine orgs used patronage jobs to maintain their influence. This worked well with the (on average) poorer Democrats, but not so well for the (on average) richer Republicans. For a middle- or upper-middle-class Republican voter, a patronage job might well have been a step down!

You’ll worry about the Republicans later. For now, it’s time to prove your loyalty by volunteering for the Democrats. And that means volunteering for your local committeeman.

Itty-Bitty City Committee

Chicago is divided into fifty neighborhood districts called wards, each with a local representative called a committeeman. And they are all men. The term won’t be officially changed to the more gender-neutral “committeeperson” until… wait for it… 2018.

This is technically an elected position, but like most local offices, in practice it’s entirely controlled by the party: becoming a candidate requires collecting so many signatures that it’s essentially impossible for anyone to gather them without a bunch of machine volunteers like you helping out.

A committeeman’s entire performance is judged on a single day: election day. Your committeeman’s job—and therefore your job as a volunteer—is to deliver as many votes as possible for the machine’s candidates.

When the machine evaluates a committeeman, their ward’s performance is all that matters. If the party gets crushed overall but does great in your ward, you and your committeeman had a great night. If the party cruises to victory but underperforms in your ward, you’re in trouble. And your committeeman sure as hell better have predicted the ward’s vote totals accurately. If he predicts the party will get 60% of the vote in the ward and it actually gets 80%, he won’t be rewarded for over-performance—he’ll be punished for his inaccurate prediction

Your first trick for getting out the vote is handing out jobs. 1960s Chicago has roughly 30,000—yes, 30,000—patronage jobs: low-level government roles that can be filled whoever the ward captain selects. That’s roughly one patronage job for every 100 residents, which means it’s pretty easy for your committeeman to hand out enough jobs that almost everyone in the ward has a cousin, friend, or neighbor who’s benefitted from his largesse.

But it doesn’t stop there: on top of the official government jobs, there are several thousand faux-patronage jobs in the private sector. These jobs aren’t technically under the party’s control, but a friendly word from a party official is usually all it takes to get someone hired. After all, the guys running these businesses either got a favor from the party already or else will want one in the future.

By the standards of the day, these are pretty good jobs: they pay decently, they provide solid benefits, and they don’t require much education, or even much work. The really good ones don’t even require showing up at all! Sure, the machine appoints some incompetent people, but as long as the incompetent remain a minority, the system keeps working. As one anonymous employer said of his ward’s committeeman: “He’s reasonable—if he sends you five guys, only two of them are illiterate.”

Of course, you can’t explicitly force people to vote for the Democratic ticket in exchange for their patronage job, but you don’t have to. The average voter in your ward isn’t particularly interested in ideology or political theory; they’ll be naturally inclined to vote for the party that’s putting them to work. Besides, they know that if the party is voted out, their employment prospects—or their cousin’s or friend’s or whatever—are likely to suffer as well.

You even get a patronage job for yourself, which somewhat eases the pain of your volunteer position being unpaid. Your committeeman probably has one too, a cushy one that leaves him lots of time for party work. If he’s extra-ambitious, he might even own a business on the side, and use his position to funnel government contracts its way.

Is this corruption? Your 2020s pre-time machine self might have thought so, but now, you and your committeeman genuinely don’t see it that way. You’re using your office to help the members of your district, which is exactly what politicians are supposed to do. Granted, you’re helping them in a scattered, ad-hoc way, but that’s just the way things go. The defining attitude of a typical machine politician is one of practicality and small-c conservatism, common to recent immigrants. Changing the system is unthinkable; better to just work it as best you can.

It’s not just through patronage jobs that you help your constituents. But you never think in terms of policy: all of your constituent service is small-bore and individualized. You and your committeeman spend your days going door-to-door, doing favors and handling complaints one at a time. You get streetlights repaired and trash cans replaced, arrange free legal services, and even give talking-tos to young miscreants. A good committeeman is basically a one-man impromptu welfare state.

The best ones go above and beyond to a degree well beyond anything one can imagine a modern politician doing. Don’t Make No Waves gives the example of a committeeman who accompanied a new immigrant on seven separate trips to various government offices to help her get citizenship. Another spent multiple days sifting through trash at the dump to find a wad of cash one of his constituents accidentally discarded, a level of service that guy who threw out 8,000 bitcoins can only dream of.

As Election Day approaches, your get-out-the-vote operation shifts into full gear—and it puts those automated texts from Nancy Pelosi to shame. Here’s how one committeeman, Arthur Varchmin, delivers a dominant Democratic performance in his ward:

Varchmin started working on his voters a year ago. He informed them all, verbally and by letter, that the city budget was being reduced by the mayor and that next year their property taxes would be lower.

Meantime, Varchmin went to the city map department, obtained the legal description of every parcel of property in his precinct, some 208 in all. Then he went to the county assessor's office and got the tax bill for each. Only four of the 208 were increased. He then reminded his voters that what he had told them a year ago about their taxes was true.

“Some tried to argue with me, but I produced the figures right on the spot.”

The Chicago City Council Retirement Home

When you fantasized about time travel as a kid, you always thought you’d hang out with Socrates in ancient Greece, or maybe give the old kill Hitler thing a try. At the very least, you thought you’d at least get to meet your past self and give them some heartfelt, life-altering advice.

But now that it’s actually happened, all you want to do is move up the ranks of local government. With your ward service complete and your loyalty proven, it’s time to run for City Council. Though “run” is a bit of a misnomer: the party agrees to slate you, which means you barely even need to campaign2.

A councilman’s job is so easy that it makes being an Account Strategist at Google look like being an Alaskan crab fisherman. Unless you’re one of the mayor’s top two or three lackeys, you can pretty much get away with doing absolutely nothing. Here’s how the Chicago Tribune described a typical council meeting in 1965:

Alderman Thomas Keane arrived 11 minutes late for a meeting Tuesday morning of the council committee on traffic and public safety, of which he is chairman. The committee had a sizeable agenda, 286 items in all to consider.

Ald. Keane took up the first item and, without calling for a vote, he declared the motion passed. He followed the same procedure on six more proposals. Then he put 107 items into one bundle for passage, and 172 more into another for rejection, without a voice other than his own having been heard.

Having disposed of this mountain of details in exactly ten minutes, Ald. Keane walked out. The rest of the aldermen sat around looking stupid.

If the position comes with no real responsibilities or influence, why do you even want to be a Councilman? Most likely, you want to make some money—maybe you own a business and use your government connections to help it grow, or maybe you just trade favors the old-fashioned way. Or maybe you’re motivated less by money and more by getting to feel like a big shot. As a councilman, you get to walk at the front of all the parades, and everyone in your neighborhood knows who you are and sucks up to you. The position doesn’t really come with any formal legislative power, but it comes with a lot of informal social power.

It also comes with de facto immunity from all but the most serious crimes. Longtime alderman Paddy Breuler once shot two cops in a bar fight—because, he claimed, they called him “a fat Dutch pig”—and suffered no consequences. Violence involving aldermen is common, as they often got themselves mixed up in various shady situations. That’s why in 1967, a newspaper reporter wrote: “This was a good year for the City Council. Only 4% of aldermen were shot.”

Nowadays, it’s usually assumed that an ambitious local politician plans to use their seat as a springboard to state or national office. But not you: like pretty much all machine politicians, your sights stay local. Not that you really have a choice: your association with the grimy corruption of Chicago politics would be radioactive at the state or national level.

But staying local is the rational move anyway, given your motivations. For those who care less about power, and more about money and social climbing within their community, then sticking to local politics is better. It provides more money-making opportunities and more of the direct connection with your constituents that you, as a social gadfly, thrive on3. As one party politician said, explaining why he didn’t care about higher office, “How many jobs does a U.S. Senator have to give out anyway?”

Besides, chances are you’re just a parochial, local-minded guy. You’ll probably die in the same neighborhood you were born in, surrounded by fellow immigrants who share your background and ethnicity. It would never occur to you to move somewhere else. It might not even occur to you to take a vacation outside of Illinois. You identify first with your neighborhood, then with Chicago, and only lastly with the United States as a whole.

And then, of course, there’s this: if you run for higher office, you might lose. As a councilman, as long as you don’t cross the machine, you can probably die in office—unless you get shot in a bar fight, beaten up in a street brawl, or blown up by a car bomb (all real things that happened to Chicago machine politicians).

Though the City Council is ostensibly nonpartisan, the machine uses its power over the Board of Elections to make sure that only its candidates have a shot, primarily by scheduling elections in ways that intentionally depress turnout. This ensures that only two groups of people bother going to the polls: the true believers and those brought there by the machine’s extensive get-out-the-vote operation.

As a result, out of 68 aldermen, only a handful are Republicans or independent-minded Democrats. The vast majority are loyal rubber-stampers like you.

King Richard

The man you and your fellow aldermen are rubber-stamping for is Chicago’s longest-serving mayor, six-termer Richard J. Daley4. Daley didn’t create the machine, but he consolidated it and, in many ways, came to define it. Like you, he started as a ward committeeman and worked his way up through the system, becoming both mayor and, simultaneously, the head of the official party organization.

Daley is the platonic ideal of a machine politician. He’s obsessed with his work and with Chicago—as a fellow lawmaker said, “Daley loves this city like you love your wife and kids. He considers Chicago his city and he doesn’t want anyone else to screw it up.” His entire “personal life,” to the extent he can be said to have one, is based around Chicago politics: he has no friends, only constituents, and he sees them not as a faceless body politic but as individual people he can relate to one by one. He attends every parade, luncheon, or ribbon-cutting ceremony he can possibly get invited to, and he fucking loves it.

Daley is an honest guy, at least by the standards of Chicago politicians (three of his four immediate predecessors had major corruption scandals). Sure, he engages in his fair share of machine patronage: over 100 of his relatives have government jobs, and he gets a highway named for an old buddy with no notable political or civic accomplishments. But he doesn’t steal from the city or conspicuously enrich himself. In fact, throughout his whole mayoralty he lives in the same blue-collar area he grew up in.

The Daley governance strategy is hard-nosed and cynical. The key is to focus on uncontroversial material issues, like building infrastructure, and to avoid addressing, or even mentioning, anything related to ideology or political philosophy. If a controversial issue becomes so salient that silence is untenable—as ends up happening with civil rights—you slow-walk it by punting it to a committee and hoping the public has a short memory. If all goes well, by the time the committee issues its recommendation, the issue will be out of the headlines and everyone will have moved on.

You’ll never be LBJ or FDR if you govern like this—hell, you won’t even be George H. W. Bush. But if you play your cards right, you can stay in office forever, and that suits Daley just fine. Like most machine politicians, his number-one goal is self-preservation.

Rage Alongside the Machine

Given that it’s the sixties, it occurs to you that maybe you should try the counterculture. You consider taking up yoga, dropping acid, or buying a VW Bus, but then you remember that as a Chicago politician, the most radical thing you could do would be to become a Republican.

Remember the Republicans? So far, we’ve given them as much space in this essay as they occupy in local politics: basically none. There are usually only one or two on the city council, and they don’t last long. But outside the city limits, the GOP has a lot of power, regularly controlling the state senate, governor’s office, and presidency. It doesn’t take a psychedelic revelation to think maybe they should try using some of that power to take a crack at the machine.

But they never really do. This is the most counterintuitive fact about the machine: it relies on the tacit cooperation of state and national Republicans to maintain its power.

Despite how it may look at first glance, the status quo actually isn’t too bad for the Republicans. The machine is Democratic, but it’s hardly liberal. It rarely pushes left-wing policies, and it’s quite friendly to corporate interests. As the Chicago Tribune once wrote, “With Mayor Dick Daley, who needs a Republican?” On the rare occasion when an ambitious Republican politician in the city does gain some traction, the machine’s non-ideological nature means it can usually co-opt them by convincing them to switch parties. They won’t even have to change that many of their policy positions.

And beyond the city limits, the machine isn’t even all that partisan. It only cares about Democratic victories in offices that are essential for its own self-perpetuation: it keeps an iron grip on the state attorney’s office, which could cause legal trouble, but it doesn’t really care if the governor or president is a Republican. To stay on good terms with national Republicans, the machine even has an official policy of supporting every president, regardless of party, on all issues not important to its local interests. Daley, for example, supports the Vietnam War to the very end, and is vocally against the New York Times publishing the Pentagon Papers.

Most importantly, though, Republican officeholders fear the unpredictable nature of political change. Once a reform wave gets going, who knows where it’ll end up? One day you’re Louis XVI, calling for a new constitution to solidify your power; the next day, a mob storms the Bastille and your head is separated from your body. A predictable electorate benefits the insiders in both parties, and any change that pushes machine Democrats out of office might end up with Republican incumbents getting thrown out too. Even if such a change would benefit the Republican party in the long run, it’s not in the interests of any individual Republican officeholder.

Not With a Bang

By now, a decade has passed since that time machine sent you tumbling back through time and space. It’s 1975—the year of Don’t Make No Waves’ publication. You’ve become a wealthy and successful Chicago politician, secure in your position, your old life in the year 2024 but a distant memory. The words “Candy for Breakfast” no longer have any meaning to you, and the idea of putting ketchup on a hot dog has become inconceivable.

You can’t imagine Chicago without the machine, and neither can Don’t Make No Waves author Milton Rakove, who confidently predicts that the machine isn’t going anywhere. Yet only a year later, Daley will die, setting off a chain of events that will end in the machine’s disappearance. Within a decade, it’ll be greatly diminished; another decade later, it’ll be gone entirely.

As in a Greek tragedy, the machine has unknowingly sowed the seeds of its own decline. As its immigrant base gets richer, they—and especially their children—will move up the political version of Maslow’s hierarchy. No longer focused entirely on securing their place in America, they’ll begin to develop stronger ideological beliefs, which means they’ll be less inclined to vote based on handouts alone. Soon, they’ll begin to crave not only material success but respectability, which the machine can’t provide.

Meanwhile, Chicago’s growing Black population will begin to want more than just the occasional Black machine representative, and the increasing salience of civil rights will make the Daley strategy of ignoring controversial issues impossible. Simultaneously, white flight will send much of the machine’s traditional ethnic base out into the suburbs, outside its grasp.

All this will happen as the national Democratic and Republican parties get deeper into the long process of polarization kickstarted by LBJ’s passage of the Civil Rights Act. When ticket-splitting is common, the machine can get people to vote for its candidates locally, even if they vote Republican for governor or president. But as people begin to vote more consistently on party lines, the machine will find itself less able to remain immune from national trends.

Besides, the machine’s leaders, always parochial, are getting old, and they’ll be distracted by infighting after Daley’s death. Perhaps a vibrant, forward-thinking machine could see these trends coming and adapt. But even if they could stave off their decline temporarily, a more educated populace and greater media scrutiny will make the death of the machine inevitable.

Or at least, that’s what most historians say.

It’s hard to imagine a machine like Chicago’s existing today. But if you squint, a version of the machine dominates the politics of the 2020s: the one-man machine named Donald Trump. Sure, he’s not a master organizational tactician like Mayor Daley. But a lot of the other similarities are there: he uses politics for his personal enrichment, prizes loyalty above all else, and his ideology—to the extent he even has one—is driven primarily by the need for political survival. He even hands out “patronage” jobs to his family members!

Trump’s Twitter account is today’s version of a classic machine politician’s forging of individual connections with their voters: both eschew traditional media in favor of more personal bonds. In the modern era of social media and anti-establishment sentiment, the machine could never be a faceless organization. It’d have to be a celebrity-driven cult of personality. And it’d look a lot like Donald Trump.

Don’t Make No Waves, Don’t Bother With This Book

Just as the machine can’t last forever, neither can the time travel gimmick I’ve been using to frame this review, which I will now leave behind to share some thoughts on the book itself.

I picked up Don’t Make No Waves, Don’t Back No Losers because “the machine” is one of those terms I’ve heard repeatedly over the years without ever really understanding what it meant, beyond a vague association with cigar-chomping guys in pinstripe suits. I was curious to learn more, and I suspected, accurately, that machine politics might involve some entertaining stories.

I appreciated the fact that Don’t Make No Waves is a firsthand account, but its insider nature left me with a lot of unanswered questions. It’d make a great handbook for my imaginary time traveler, but as someone who moves through time the normal way, I wanted more than I got. For example, the book is conspicuously silent on how the machine got started in the first place, which I imagine is a pretty interesting story. It also doesn’t engage at all with other cities’ machines—how were they similar to, or different from, Chicago’s, and why did they die long before its did? In a way, Don’t Make No Waves is as parochial as the politicians it describes.

Also like its subjects, Don’t Make No Waves is surprisingly uninterested in actual governance. I appreciated that the author didn’t waste time moralizing about the machine’s ethics, but I wanted to know more about how well the machine actually ran the city. The author repeatedly asserts that Chicago is no worse-governed than any other big American city in the 1970’s (admittedly, incredibly faint praise), but never provides any evidence.

Without a sense of the machine’s effectiveness at actually governing the city, it’s impossible to judge how much its corruption mattered. I came away from the book grateful that most government jobs no longer go to some random politician’s cousin, but I also came away with a different emotion: envy. I was left longing for a Democratic party that’s as organized and competent as the one described in the book5.

Because ultimately, that’s what I wanted to know: were the trade-offs of machine politics in any way worth the results? Could we possibly bring back some of its positive elements without all the downsides? If a little more corruption and graft is what it takes to get there, that’s a trade I might be willing to make.

I still don’t feel like I have the answer to that question, but I’m grateful to have learned more about what politics was like during other times in this country’s history. Such knowledge is always interesting, but it’s especially relevant today, when every election involves talk of American democracy itself being on the ballot. When I remind myself that “American democracy” has had many different meanings throughout this country’s short history, my nightmares are soothed. I may still have unanswered questions about the machine, but at least I’m sleeping better.

Wow—you made it all the way to the bottom! If you liked this piece, give the a heart button at the bottom a tap to let me know. You might also enjoy my other long pieces about political books:

Public Interest Law and the Paradox of Justice by Lawsuit, in which Ralph Nader kickstarts a new kind of political activism and accidentally paralyzes the government

Book Review: The Outlier, about the life and legacy of Jimmy Carter

Two other factors contribute to the disproportionate Irish representation in Chicago and other cities. First, many of the first wave of immigrants ran local gathering places like bars and taverns, which gave them a head start forming local connections. Secondly, the Irish are mostly immune from the factional rivalries and prejudices that many immigrants from continental Europe brought over with them.

I’ve oversimplified things for this essay. In reality, in between volunteer and councilman, you might have served as a committeeman yourself, or held an administrative office like treasurer or county assessor. (Despite their unassuming names, these were actually the seats of significant power.)

This is decidedly no longer true today, when national politicians can use the internet and social media to connect directly with their constituents, and can easily get rich once leaving office with a cushy think-tank job or a spot as a TV commentator.

His record will later be beaten by his son, Richard M. Daley, who’ll also serve six terms (from 1989–2011), but who’ll slightly outlast his father by completing his final term instead of dying in office.

Note: I wrote this line before Biden dropped out. Maybe the Democratic party is more organized and competent than I thought!