What I've Been Reading About the Election

Hey everyone,

On Tuesday night, as I was frantically watching one set of numbers on my phone, a very different number came in: this newsletter officially crossed 1,000 subscribers.

I guess humans are suckers for nice, round numbers, because somehow 1,000 of you feels like a much bigger responsibility than 999. If it takes ten minutes to read one of my essays, then every time I hit publish, I’m potentially wasting almost seven days of cumulative reader time1.

It’s not the biggest audience in the world or anything, but it’s enough that I can feel myself starting to stress about each piece more—to make sure everything is polished, without too many typos or poorly thought out opinions I’ll later regret.

Actually, though, I want to push in the opposite direction, and make sure this newsletter remains loose and experimental. One thing I want to play around with more is sending some posts that are a bit more casual and less polished than what I usually write—less “here is an essay I revised many times” and more “hey guys it’s me writing you an email.”

In that spirit, I thought that rather than writing my own take on the election—because honestly who needs that—I’d share some of the most interesting and helpful stuff I’ve been reading over the past few days

The second COVID election. If you want a simple, clear take on the results, so far I like The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson’s the best:

Trump’s victory is a reverberation of trends set in motion in 2020. In politics, as in nature, the largest tsunami generated by an earthquake is often not the first wave but the next one.

It’s a cliché to link to him at this point, but Ezra Klein’s is pretty good too, especially the analogy to 2004.

Relatedly, via the Financial Times’ John Burn-Murdoch, this is the first time since WWII that every governing party facing election lost votes. Politics are globalized too now.

If you want a more cynical opinion, read this one from by far my favorite person on Substack, Sam Kriss. I don’t fully endorse this take—I’m not even sure Sam himself fully endorses it—but damn if it isn’t entertaining:

The reason Kamala Harris lost is the same as the reason she was the candidate to begin with: the Democratic Party is allergic to democracy. It’s the instrument of a particular form of class power; its role is basically disciplinary. When it comes to an actual crisis, all it knows how to do is coil in on itself, breathe in its own fumes, suck itself off until completion. The party knew that Joe Biden’s brains kept running out of his nose and into his morning coffee, but they kept pretending until it was far too late that he was running laps around the White House lawn and solving new problems in theoretical physics in his spare time.

Trump’s luck. Back in July, I wrote:

This summer has seen Donald Trump hit a string of lucky breaks so unlikely that I’m starting to wonder whether we’re all just NPCs in his simulation. Either that, or God is real, and he’s a Trump fan. We’re speedrunning that famous Marx quote, with history repeating itself as both tragedy and as farce at the exact same time. If he somehow manages to lose this one, he’ll be the Republican nominee in 2028, 2032, and every four years thereafter until he dies. If he dies. At this rate, he’ll probably be the first person to live forever.

And that was before he survived two assassination attempts and won re-election. In retrospect, his losing in 2020 was actually its own form of lucky break. His political legacy is now more far more impressive than if he’d just won a regular reelection, and as RFH points out, he skipped over the bad part of the post-COVID economy and is poised to inherit the good part:

Then again, part of the reason Trump seems so lucky is that he continually creates opportunities for new lucky breaks by squandering the previous one. So we’ll see.

Tech & Trump. The PayPay mafia is a group of PayPal founders who have since become disproportionately successful in the tech industry. With Elon Musk in Trump’s ear and Peter Thiel’s protege JD Vance as VP, they have now become disproportionately successful in politics as well. (The right-wing ones, at least—the left-wing ones, like Reid Hoffman and Yelp founder Jeremy Stoppelman, are shit out of luck.)

To Substack cofounder Hamish McKenzie, Elon is an amped-up version of the news tycoons of the early 20th century, who craved power and made no pretense to editorial neutrality—“Rupert Murdoch and William Hearst on amphetamines.”

What are Elon and Trump’s other Silicon Valley supporters thinking? I like Rippling founder Parker Conrad’s take:

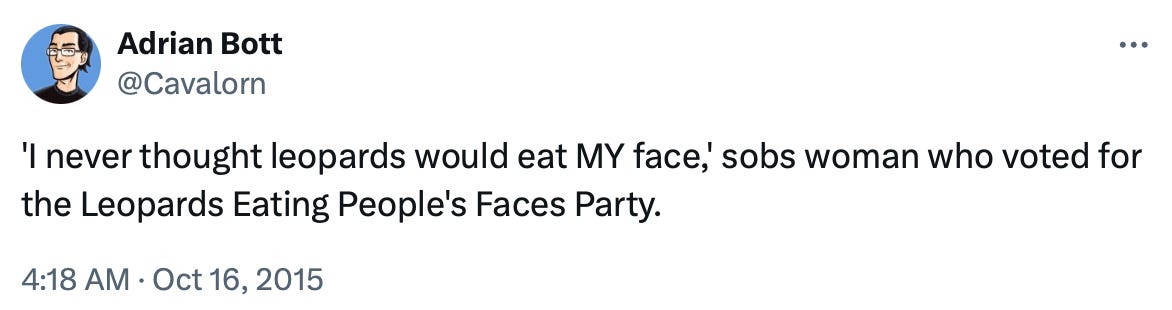

My personal view is that a lot of smart people are being very stupid and believe that Trump is going to do THEIR thing. Tech people think he will usher in a new, tech-forward, business friendly environment. Kooky fluoride conspiracy theorists think he’s gonna take care of that thing. Etc. I think they will all be disappointed when their faces get ripped off. It’s weird because Trump being elected feels like the end of the world but there are all these very smart people who I like and respect who think it’s gonna be the best thing ever. So, 🤷. I hope they are right.

The past eight years have taught us all not to make overly-confident political predictions, but there is one prediction I feel very confident registering here: Trump and Elon will have a full falling out by 2028.

Facial hair in the White House. Speaking of JD Vance, he’s the first president or vice president to have facial hair in almost 100 years, since Herbert Hoover’s VP Charles Curtis. (Harry Truman briefly grew a goatee on vacation, but shaved it off before returning to work.)

Beards may be back, but as Eric Hovde’s loss to Tammy Baldwin in Wisconsin proves, mustaches are still electoral poison everywhere but Maine.

Actually, I take back everything I wrote earlier. The only election commentary you need is this tweet:

Alright gang—that’s it for today. If you want more of this kind of thing (casual, tossed-off posts, links to stuff I’m finding interesting, etc), let me know with a like or a response. And a huge thank you to all 1,001 of you for reading.

Good luck with the next four years,

Max

This math is pretty loose, because only around half of you actually read any given email, but then also lots of people who aren’t subscribers read. But you get the idea.